Carnatic Compositions You Should Know | The Core Repertoire

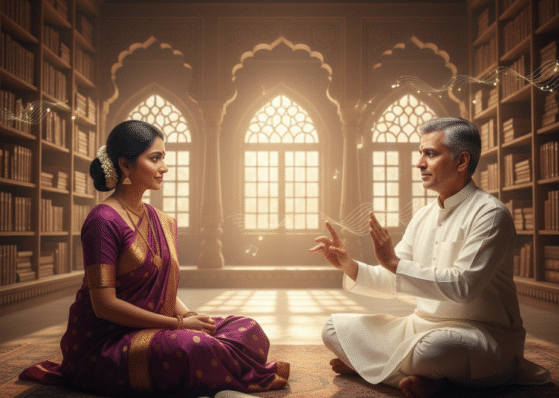

Carnatic music, the classical music tradition of South India, is far more than a system of ragas and talas. At its heart lies sahitya—poetry set to melody—and Carnatic compositions that have carried devotion, philosophy, and musical brilliance across centuries. These Carnatic compositions are not merely performed; they are lived, revisited, reinterpreted, and cherished by musicians and listeners alike.

For someone beginning their journey into Carnatic music—or even for seasoned rasikas—certain Carnatic compositions serve as important landmarks. They appear repeatedly in concerts, classrooms, and daily practice, each revealing something essential about the tradition. Let us explore some of these popular Carnatic compositions and understand why they continue to hold such a central place in the musical landscape.

The Foundation of Carnatic Compositions | The Trinity’s Enduring Works

Any discussion of popular Carnatic compositions inevitably begins with the Trinity: Tyagaraja, Muthuswami Dikshitar, and Syama Sastri. Their works form the backbone of modern Carnatic repertoire, and their influence is so deep that even contemporary compositions often echo their stylistic choices.

Tyagaraja’s kritis, in particular, are widely sung and deeply personal. Written mostly in Telugu, his compositions express an intimate, emotional relationship with Lord Rama. Songs like “Endaro Mahanubhavulu” (Sri raga) and “Rama Nannu Brovara” (Harikambhoji) are staples of the concert platform. What makes Tyagaraja’s compositions so enduring is their balance—melodic beauty, rhythmic clarity, and heartfelt devotion coexist effortlessly.

Transitioning from Tyagaraja’s emotive simplicity, Muthuswami Dikshitar offers a contrasting aesthetic. His compositions, primarily in Sanskrit, are expansive and majestic. Kritis such as “Vatapi Ganapatim” (Hamsadhwani) and “Akshayalinga Vibho” (Sankarabharanam) showcase his mastery over raga structure and his scholarly approach to music. Dikshitar’s works often unfold slowly, inviting the listener into a meditative space.

Syama Sastri, though fewer in number, contributes compositions of intense emotional depth. His kritis, like “Devi Brova Samayamide” (Chintamani), are marked by complex rhythmic patterns and an earnest plea to the divine feminine. Together, the Trinity’s compositions create a foundational grammar that defines Carnatic music as we know it today.

Varnams | The Gateway to Carnatic Music

Before diving into kritis, most students of Carnatic music encounter varnams. These compositions play a dual role: they are both pedagogical tools and concert openers. A varnam encapsulates the essence of a raga, presenting it in a structured yet vibrant manner.

Take “Viriboni” in Bhairavi, attributed to Pacchimiriam Adiyappa, or “Vanajakshi” in Kalyani by Pallavi Gopala Iyer. These varnams are not just exercises; they are miniature masterpieces. Through repetitive yet varied phrases, they allow the musician to explore raga grammar while building stamina and precision.

In concerts, varnams serve as a warm, confident entry into the performance. They set the tone, establish the raga, and immediately engage the audience. Over time, listeners begin to recognize these pieces, associating them with certain moods—Bhairavi’s grandeur or Kalyani’s auspicious brightness.

Carnatic Compositions That Define the Modern Concert Experience

As a Carnatic concert progresses, kritis form its emotional and intellectual core. Certain compositions have become almost synonymous with the concert experience itself.

“Brochevarevarura” in Khamas, for instance, is frequently rendered with lively swara passages, making it a favorite among performers and audiences. Similarly, “Nagumomu Ganaleni” in Abheri captures longing and vulnerability in a way that resonates deeply, even with listeners unfamiliar with the language.

These compositions endure not because they are easy, but because they invite endless interpretation. A single kriti can sound vastly different depending on the artist’s approach to raga alapana, neraval, or kalpana swaras. In this sense, popular Carnatic compositions act as shared texts—common ground upon which individual creativity flourishes.

The Emotional Range of Carnatic Compositions Beyond Devotion

One of the remarkable aspects of Carnatic compositions is their ability to transcend linguistic boundaries. While Telugu, Sanskrit, and Tamil dominate the repertoire, the emotional content often communicates directly, even to those who do not understand the words.

Consider “Bhaja Govindam”, attributed to Adi Shankaracharya. Though originally a philosophical hymn, its Carnatic renditions bring out urgency and compassion, reminding listeners of life’s impermanence. Similarly, Tamil compositions like “Kurai Ondrum Illai” by C. Rajagopalachari have gained immense popularity for their universal message of gratitude and surrender.

This devotional aspect does not feel restrictive or dogmatic. Instead, it acts as a bridge—connecting performer, listener, and composer through shared emotion. That is why these compositions continue to appear in concerts across generations.

Javali and Padam| The Subtle Side of Expression

Moving away from overt devotion, Carnatic music also embraces compositions that explore human emotion in more intimate ways. Padams and javalis focus on sringara (romantic and emotional expression) and require a refined sense of bhava.

Padams like “Yarukagilum Bhayama” in Begada are slow, nuanced, and introspective. They demand restraint from the performer and reward the listener with layers of emotional meaning. Though not as frequently performed as kritis, these compositions hold a special place, especially in dance and thematic concerts.

Their popularity may be quieter, but their impact is profound, offering a reminder that Carnatic music accommodates tenderness and vulnerability alongside grandeur.

Why These Compositions Continue to Matter

What unites all these popular Carnatic compositions is their adaptability. They have survived not because they are frozen in time, but because they allow space for reinvention. Each generation of musicians adds its voice, subtly reshaping how a familiar kriti is heard.

Moreover, these compositions act as cultural anchors. In a rapidly changing world, they offer continuity—linking today’s concerts to centuries-old traditions. For listeners, they become markers of memory: the first concert attended, a beloved teacher’s rendition, or a line of sahitya that lingers long after the music fades.

Closing Thoughts

To know Carnatic music is, in many ways, to know its compositions. Ragas and talas provide the framework, but it is through kritis, varnams, padams, and javalis that the tradition truly speaks. The popular compositions you hear again and again are not overused—they are well-loved, revisited across generations in classrooms, concerts, and learning spaces such as The Mystic Keys, where Carnatic vocal lessons online allow students to engage deeply with these timeless works.

Whether you approach them as a student, performer, or rasika, these compositions invite you into an ongoing conversation between past and present. And the more you listen, study, and sing—guided by structured learning or personal exploration—the more you realize that each familiar song still has something new to say.

For more information and exciting resources about learning music, visit our website at The Mystic Keys. For more music content and exciting offers follow us on

Facebook, Instagram, YouTube, LinkedIn, Twitter, Pinterest, and Threads.